INTRODUCTION

The oral cavity, head and neck regions possesscomplex, rich and intricate blood vessels whichmight be a predisposing factor for a variety ofvascular lesions. These lesions represent the mostcommon growths in infancy and childhood, and mayvary from small innocent birthmarks to largedisfiguring tumours. Based on their clinicalbehaviour and the endothelial cell characteristics.1, 2 these lesions have been recently categorized intotwo groups as vascular malformation orhemangiomas. It is agreed that vascular lesions originate from a persistent angioblastic tissue thatis characteristic of two-stage process growth andregression.1

Hemangiomas are most common tumors foundin childhood with predilection to head and neckregion up to 60%.3, 4 The most common sites beinglip, vermilion border, tongue, salivary glands. Hemangiomas usually appear 2-4 weeks after birth, grows rapidly till the age of 6-8 months and thenslowly. By age 5-8 years, they start to involute andspontaneously regress in 70% of the cases.5 Theyare characterized on the cellular level by increased endothelial cells turnover, a number of mast cellsduring rapid growth phase, diminished cellularitywith fibrous tissues and low mast cell counts duringinvolution.5 The present paper discusses a case oftongue hemangioma treated with excision androtational advancement flap.

CASE HISTORY

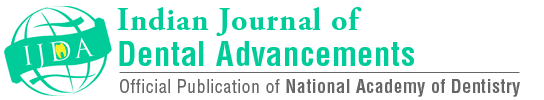

An 8-year-old boy was referred for evaluationof a growth that was present on the dorsum of rightside of the tongue that had been clinically apparentfor approximately 1 year. Patient reported that thearea was easily traumatized by eating, withsecondary swelling and occasional bleeding. Thechild had a normal medical history with no unusualfindings in relation to the mother’s pregnancy, labor, or delivery. His family history was noncontributoryand on physical examination he appeared to behealthy and of normal size and weight. At the timeof presentation, the lesion continued to besymptomatic. On physical examination of the oralcavity, there was a 4.5-cm red and purple vascularlesion that involved less than one half of the tongue. Oral examination demonstrated the lesion withenlarged papilla on dorsum of tongue and tonguetie present (Figure 1). After photographs were takenthe written consent was obtained. The clinical endpoint was blanching upon pressure. The surfaceappeared to be smooth and hyperkeratotic with agray hue that blanched slightly under pressure. Thelesion was soft to palpation. The remainder of theoral examination was essentially normal. No positivecervical lymphadenopathy could be detected.

|

Figure 1: Clinically lesion is seen with enlarged papilla ondorsum of tongue.

Click here to view |

Ultrasound and Doppler imaging showed ill-defined heterogenous lesion, largely hypoechoic, seen on left side of the tongue in sub mucosal region. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as ahemangioma, and the selected treatment was theexcision of lesion and rotational advancement flapfor closure of the defect. The signs ofrevascularization after finger pressure weredetermined and no pulsations were obtained fromthe lesion and the lesion was diagnosed ashemangioma.

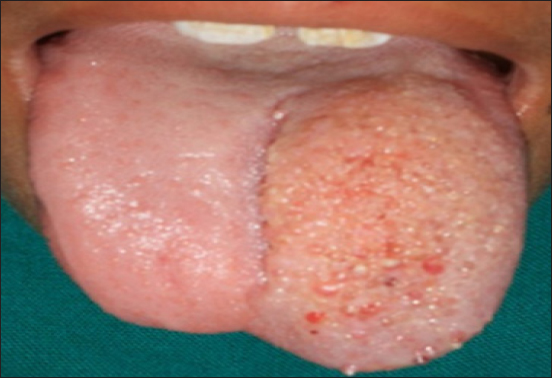

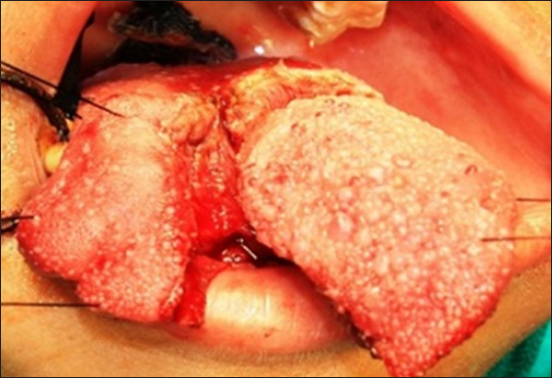

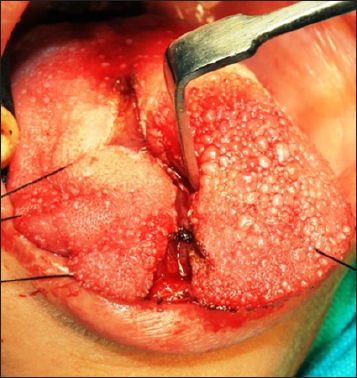

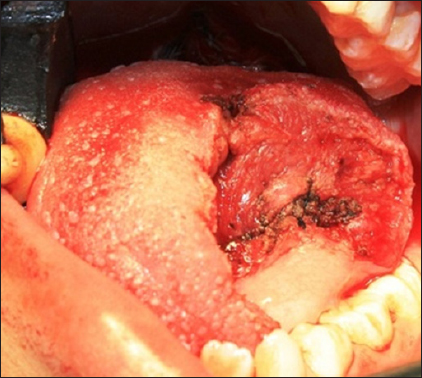

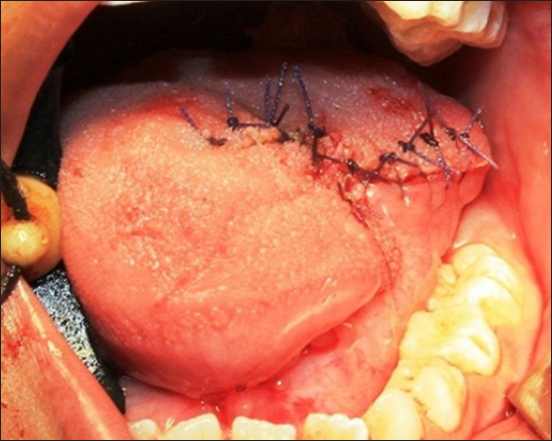

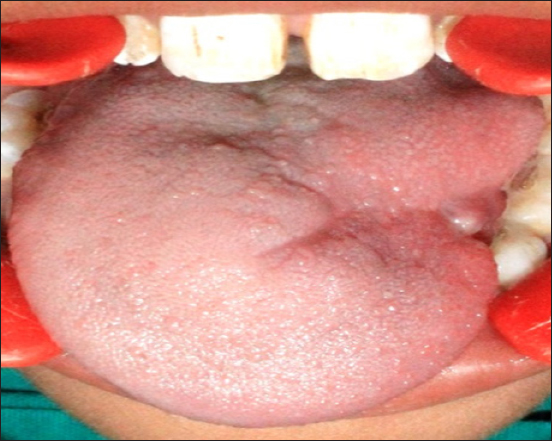

Under General Anesthesia the surgery wasperformed. Initially tongue tie was released. Tongueprotruded to normal movement. 3-0 silk sutureswere used to retract for better accessibility andexposure of lesion (Figure 2). By using monopolarelectro cautery total excision of lesion was done, lingual artery was identified and ligated (Figure 3 and 4). Using rotational flap i.e. anterior part oftongue of other side, the defect was approximated(Figure 5). Suturing was done by using 3-0 vicrylsuture (Figure 6). Recovery was uneventful. Histopathologically the excisional biopsy diagnosedas cavernous hemangioma. Microscopicallyconnective tissue stroma showed large dilated bloodfilled cavities lined by plump endothelial cells. Threemonths postoperatively patient was examined fortongue retrusion, protrusion and lateral movementsand functional and aesthetic requirements wereachieved (Figure 7).

|

Figure 2: 3-0 silk sutures were used to retract for better accessibility and exposure of lesion.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 3: Lingual artery is identified and ligated.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 4: By using monopolar electro cautery total excision of lesion was done.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 5: Using rotational flap i.e. anterior part of tongue of other side, the defect was approximated.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 6: Suturing was done by using 3-0 vicryl suture. Three months postoperatively patient was examined for tongue retrusion, protrusion and lateral movements and functional and aesthetic requirements were achieved (Figure 7).

Click here to view |

|

Figure 7: Three months postoperatively, patient was examined for tongue retrusion, protrusion and lateral movements and functional and aesthetic requirements were achieved.

Click here to view |

DISCUSSION

The widespread belief that hemangiomas willcompletely disappear in the frist few years of life ismisleading, as shown by Finn et al who reportedthat 80% of lesions that had not involuted by 6 years(and 38% of lesions that had involuted at 6 years)left behind a residual cosmetic deformity.6 Thepsychosocial trauma of a visible lesion in a growingchild, and the poor outcome of benign neglect, takenwith the current availability of drugs, lasers, andother techniques to treat these lesions safely, shouldwarrant a change in the philosophy of “benignneglect”.6-9

A useful approach to the management of hemangiomas can be based on the stage of the lesion(proliferative or involutive phase), type of lesion(supercial, deep, compound) and the managementof residual deformity.10, 11 In general, life-threateningand sight-threatening hemangiomas should be dealtwith, regardless of the stage of the lesion. Activeintervention should be considered in all disfiguringhemangiomas, but each case should be managed onits merits after careful discussion and counselling, to prevent potential psychosocial trauma andcosmetic deformity.10, 12, 13

Table 1

Current classication of haemangioma andvascular malformations 14

A. Hemangiomas

Supercial (capillary haemangioma)

Deep (cavernous haemangioma)

Compound (capillary cavernous haemangioma)

B. Vascular malformations

Simple lesions

Low-flow Lesions

Capillary malformation (capillaryhaemangioma, port-wine stain)

Venous malformation (cavernoushaemangioma)

Lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma)

High-flow Lesions

Arterial malformation

Combined lesions

Arteriovenous malformations

Lymphovenous malformations

Other combinations

The diagnosis and the classification of thevascular malformations have a great importance onthe treatment plan of the lesions. Mulliken andGlowacki proposed a terminology for classifyingthese lesions that is based on clinical andmicroscopic features.1 This system broadly classifiesvascular lesions into hemangiomas and vascularmalformations. The hemangioma is the truevascular tumor that results from a neoplasticovergrowth of normal vascular tissue. Thehemangioma grows by endothelial proliferation. Indistinction to hemangiomas, vascular malformationsresults from abnormal vascular or lymphatic vesselmorphogenesis, not as the result of abnormalendothelial growth. Hemangiomas are usuallypresent at birth and can be diagnosed by 1 year, whereas vascular malformations are present at birthbut often not diagnosed until second decade of life. The three stages in the life cycle of a hemangioma, each characterized by a unique assemblage ofbiologic markers and processes, are (1) theproliferating phase (0-1 year of age), (2) theinvoluting phase (1-5 years of age), and (3) theinvoluted phase (>5 years of age).15 Vascularmalformations show slow growth throughout lifewith increase in response to infection, trauma, orhormonal fluctuation and they do not involute.16, 17Osseous involvement of the hemangiomas is rarebut 35% of the vascular malformations show osseousinvolvement.18

Although most hemangiomas of the tongue areasymptomatic, they could sometimes causesignificant bleeding, pain or difficulty in chewing, speaking, and even swallowing, if they are largeenough. Small lesions can be excised. Large lesions, if excised, could result in significant functionaldisability. This is why several modalities of lessinvasive treatment have recently been advocated(Argon laser, Nd: YAG laser, or both to avoidfunctional disability caused by tissue loss). Also, there have been reports of treatment with superselective embolization using polyvinyl alcohol foam(Ivalon) and absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam)particulates.

Although hemangiomas are common in infancyand childhood, they are probably developmentalabnormalities rather than true neoplasms. Pathologists distinguish three classes: capillary, cavernous, and mixed types. Cavernoushemangiomas are blue, soft, spongy masses that arenot encapsulated. Some hemangiomas of the tonguehave a lymphangiomatous component, hence thename hemangiolymphangiomas.

INVESTIGATIONS

Ultrasonography and color Dopplerexamination are inexpensive and non-invasiveimaging techniques and are used most commonlyto confirm the diagnosis.19-21 Grey-scale ultrasoundand Doppler analysis are a useful in determiningwhether the lesion is solid or cystic and to establishthe presence or absence of high flow vessels. Sonography has been advocated as useful inexamining soft-tissue masses that are suggestive ofhemangiomas or vascular malformations.19, 20 Vesseldensity as depicted on Doppler sonography has beenused in differentiating other types of masses fromvascular malformation.21 Certainly, the Dopplercharacteristics of vascular malformations are helpfulin differentiating low-from high-flow vascularmalformations.22

Result

Reconstruction of a medium-sized defect of thetongue remains a challenge if functional andaesthetic impairment is to be avoided. The tonguebase island advancement flaps developed toreconstruct medium-sized defect. The size amountsto 4.5 χ 3 cm (length x width). The tongue base islandadvancement flap reduces the volume of the tonguebase without causing function impairment of thetongue. The patient recovered with good objectiveand subjective speech, swallowing and aesthetics. Patient has no local recurrence. The technique oftongue base advancement flap is ideal for functionaland aesthetic repair of medium-sized tongue defects.

CONCLUSION

A variety of methods of treatment are thusavailable for intraoral hemangiomas. The majorityof these lesions can be regarded as capillary-cavernous hemangiomas. While surgical removal oforal hemangiomas is indicated for small lesions itsuse with large lesions lead to extensive tissue defectand rapid bleeding which might be difficult tocontrol. Cryosurgery, on the other hand, is veryeffective in small superficial lesions but is completelyineffective in large deep ones. Embolization, utilizingvarious materials, is used to obstruct the vessels, with excellent results but requires considerableexpertise from the technical point of view andserious complications such as tearing the vessels andover dilatation might occur. Circumferential excisionand rotational advancement flap is therefore avaluable technique requiring minimal experiencewhile aiming at achieving normal functional andaesthetic repair of medium-sized tongue defects.