INTRODUCTION

Intrusive luxation (intrusion) is displacement of the tooth into the alveolar bone along the long axis of the tooth and is accompanied by comminution or fracture of the alveolar sockets.1

Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth is a rare injury, which in several studies has been found to represent only 0.3-2% of traumas affecting the permanent dentition.2 An intrusion represents most severe injury to the dentition through damage to the gingival attachment, contusion of periodontal ligament and bone and damage to the Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath. Moreover, the intrusive displacement of the tooth will force bacterial plaque covering the dental crown into compromised wound site. All these events individually and combined have the potential of eliciting healing complications.1

Significant controversy exists concerning the optimal treatment for intruded teeth. It has been found that intruded teeth with immature root formation may re erupt spontaneously and also in some cases with completed root formation. However, spontaneous re-eruption is unreliable.1

Unlike deciduous teeth, permanent teeth rarely undergo root resorption.3 Even in the presence of peri-radicular inflammation, resorption will occur primarily on the bone side of the attachment apparatus and the root will be resistant to it. Although many theories have been put forward, the reason for the resistance of the root to resorption is not fully understood.

One theory maintains that the remnants of the epithelial root sheath surround the root like a net, therefore imparting a resistance to resorption and subsequent ankylosis.4 However, this theory has failed to gain support, and a second hypothesis that has been put forward is more likely.5

This theory is based on the premise that the cementum and predentin covering on dentin are essential elements in the resistance of the dental root to resorption. It has long been noted that osteoclasts will not adhere to or resorb unmineralized matrix. Major mediators of osteoclast binding are RGD-peptides that are bound to calcium salt crystals on mineralized surfaces. Since the most external aspect of cementum is covered by a layer of cementoblasts over a zone of non-mineralized cementoid, a surface that provides satisfactory conditions for osteoclast binding (RGD-peptides that are bound to calcium salt crystals on mineralized surfaces) is not present. Internally, the dentin is covered by predentin matrix, which possesses a similar organic surface. Unlike the first theory, there are numerous studies which lend support to this idea.6

Another function of the cemental layer is related to its ability to inhibit the movement of toxins if present in the root canal space into the surrounding periodontal tissues. The consequence of an infected root canal space is, therefore, most likely to be apical periodontitis, as the toxins can only communicate with the periodontal tissues through the apical foramina or large accessory canals. However, if the cemental layer is lost or damaged, the inflammatory stimulators can pass from an infected pulp space through the dentinal tubules into the surrounding periodontal ligament, which, in turn, sets up an inflammatory response. Since the cementum is lost, this inflammatory response will result in both bone resorption and root resorption.6

External root resorption is one of the healing complications that occur as a result of intrusive luxation. It has been described as surface, inflammatory or replacement resorption, of which inflammatory resorption is related to necrotic and infected pulp. When dentinal tubules are exposed by the resorption of damaged tissues on the root surface, bacteria and toxins from root canal may via dentinal tubules diffuse to the adjacent periodontal tissues causing inflammation and progressive root resorption. This resorption seems to be more frequent and rapid in immature teeth, most probably due to the thin dentinal walls and wide tubules. Once bacteria have settled in the necrotic pulp, the arrest or healing of inflammatory resorption depends on the removal of bacteria from pulpal lumen and adjacent dentin tubules by endodontic therapy.1

Traumatic loss of maxillary incisors during the active teenage years is a serious and challenging clinical situation. Because of the frequency of dental trauma in infancy and childhood, traumatized teeth with various long-term prognoses pose a problem when planning orthodontic treatment.2

One of the most challenging problems in dentistry is deciding which treatment option is best, i.e. the decision to replace one or more maxillary incisors that have been lost as a result of traumatic injuries. An optimal outcome frequently involves an interdisciplinary team of experts, including periodontists, endodontists, oral surgeons, orthodontists, and prosthodontists. The treatment is typically complex and the prognosis often uncertain. There are multiple solutions available to treat this kind of problem. The ideal treatment is usually the most conservative option, in which individual aesthetics and functional requirements are met.

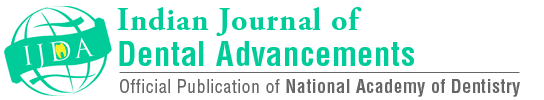

The alternative approaches include auto- transplantation, placement of a bridge or an implant during adulthood, and substitution of the ipsilateral lateral incisor for the central incisor after space closure. The choice of the appropriate solution for the missing maxillary central incisor depends on the specific characteristics of each situation (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: The order of likelihood of favorable to unfavorable healing following the different categories of luxation injuries occurring.

Click here to view |

CASE REPORT

A healthy 14-year-old girl presented herself at the Outpatient department on Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, Maratha Mandal’s Nathajirao G. Halgekar Institute of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Belgaum, with the chief complaint of mobile tooth in upper front teeth region. She reported displacement of the upper central incisors while playing two- three months earlier (Figure 2). The patient didn’t visit a dentist then, and no treatment was carried out. No other significant dental or medical history a found.

|

Figure 2: Preoperative intra oral view

Click here to view |

Percussion, palpation and pulp vitality test (cold test) were done from canine to canine and revealed the presence of increased mobility as well as absence of vitality in 21. Radiographic examination showed the presence of inflammatory external root resorption irt 21 (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3: Preoperative IOPA showing resorption

Click here to view |

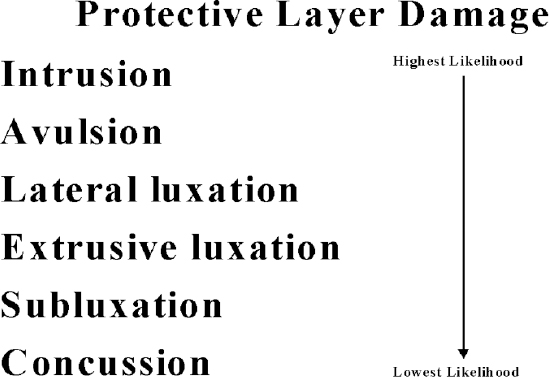

The proposed treatment consisted of dental extraction and use of a removable aesthetic prosthodontic appliance (Figure 4 and 5).

|

Figure 4: Lab procedures for the fabrication of anterior removable space maintainer

Click here to view |

|

Figure 5: Intraoral view after the denture delivery

Click here to view |

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of missing anterior teeth as a result of dental trauma is reported as 12 per 1000 children in one cross-sectional epidemiological study.7 Consequently, although rare in a growing child, failing or missing anterior teeth as a result of dental trauma is a complex area requiring specialist interdisciplinary planning and treatment.8

The choices of treatment for failing anterior teeth are dependent on the characteristics of each specific situation. The team must take into account the age of the patient, growth potential, occlusion, oral hygiene, caries status and motivation towards dental health in addition to patient compliance. The ideal outcome in the young patient with poor prognosis anterior teeth is to preserve bone and soft tissues as long as possible to improve the restorative options that can be offered in early adulthood after growth has ceased. Treatment options fall into two broad categories; retention of the maxillary incisor as long as possible or removal of the failing tooth at the most appropriate time. 8

The management of the subsequent space following tooth or crown loss in a growing patient includes replacement with a denture, resin-bonded bridge, orthodontic space closure or tooth auto- transplantation and should take into account the patient’s oral hygiene, occlusion and compliance.

A simple acrylic denture to replace a missing anterior tooth is frequently used in the paediatric population. The recommended design is a T-shaped denture with clearance of acrylic from all gingival margins and retentive clasps on first permanent molar teeth to enhance retention. They are quick and simple to make and modify and can be used in both the short (e.g. while adjacent injured teeth heal prior to the construction of a resin retained bridge) and medium term (e.g. where few other treatment options exist) until anterior alveolar growth has completed and implants may become applicable. Partial dentures do have a number of associated problems including denture induced stomatitis and dental caries where plaque control and denture hygiene is poor. Tissue borne dentures may well have a further detrimental effect on bone volume in the anterior area.9 For most adolescents, however, having no prosthetic replacement is unacceptable. Consequently, despite some of their limitations tissue borne partial dentures are still frequently used when teeth have been extracted or replantation of an avulsed tooth is contraindicated.8 Only once growth has ceased can osseo-integrated implants be provided.