Introduction

Infection with Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) was first documented in the writings of ancient civilizations as a vesicular rash of unknown causes. A relationship between herpes zoster and chickenpox was suggested in 1888 and was finally proven in the 1950s. Since then, much progress has been made in preventing and treating the disease with the introduction of a live attenuated vaccine in 1974, treatment with acyclovir in the 1980s, and complete DNA sequencing in 1986, all of which may ultimately lead to the eradication of VZV infection.1 Herpes zoster (HZ) is the reactivated form of the Varicella Zoster virus (VZV), the same virus responsible for chicken pox. HZ is more commonly known as shingles, from the Latin cingulum, for “girdle”. This is because of common presentation of HZ involves a unilateral rash that can wrap around the waist or torso like a girdle. Similarly, the name zoster is derived from classical Greek, referring to a belt like binding (known as a zoster) used by warriors to secure armor.2 Herpes zoster is caused by Varicella Zoster virus, a neuro-dermotropic virus which is distributed worldwide. It is characterized by unilateral radicular pain and grouped vesicular eruption that is generally limited to the dermatome innervated by a single spinal or cranial sensory ganglion. It occurs as a result of reactivation of the latent virus from within the sensory ganglion following an earlier attack of varicella.3-5 The reactivation of the virus may be due to immune suppression (inherited, acquired or iatrogenic) or spontaneous. In HIV patients it may present in diverse manner such as multidermatomal involvement, crusted, nodular, vesiculo-pustular, ulcerative or erythematous lesions that may be widely disseminated or localized .6-9 The most commonly affected dermatomes are the thoracic (45%), cervical (23%), and trigeminal (15%).10, 11

Materials and Methods

The present study was a prospective observational study conducted in the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology. The study was conducted over a period of 1 year from January 2015 to Feb 2016. During this period 56 clinically diagnosed cases of Herpes Zoster attending OPD were included in the Study. Ethical clearance was taken before performing the study and informed consent from patients was also taken. Patient particulars like age, sex, address and occupation were noted. A detailed history regarding prodromal and presenting symptoms, day of occurrence and types of skin lesions, the nature, severity and character of pain were noted. Past history of chicken pox if any was noted. History suggestive of any provocative factors was also sought. A thorough general physical examination and local cutaneous was done and findings were recorded. Whenever required, opinion from other specialists was sought. Complete haemogram, blood sugar, routine urine examination and ELISA for HIV 1 and 2 were done. All patients were reviewed weekly for 1 month and then monthly for 3 months. Post herpetic complications were noted in all patients. The data was tabulated and analyzed statistically.

Results

The recorded data was compiled and entered in a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) and then exported to data editor of SPSS Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical software SPSS and Microsoft Excel were used to carry out the statistical analysis of data. Descriptive statistics of data including percentages and means were reported.Graphically the data was presented by bar diagrams. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

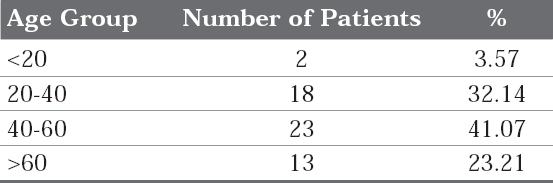

Regarding the age distribution 3.57% patients were below 20 years of age, 32.14% were between 20-40, 41.07% were between 40-60 years and 23.21 were above 60years of age. Majority of patients were in the age group of 40-60 years (Table 1).

|

Table 1 : Age distribution of the patients

Click here to view |

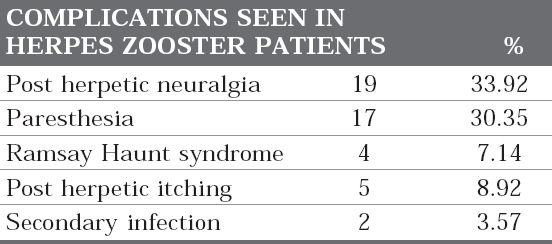

The most common complication seen in zoster patients was post herpetic neuralgia in 33.92% patients, followed by paresthesia in 30.35% patients. Post herpectic itch was seen in 8.92% of patients, Ramsay Haunt syndrome was seen in 7.14% while secondary infection was seen in 3.575 of patients. Only 9 patients i.e 16.07% does not develop any complication and healed un eventfully (Figure 1 and 2) (Table 2).

|

Figure 1 : Patient showing extraoral presentation of herpes zoster

Click here to view |

|

Figure 2 : Patient showing complete recovery of Herpes Zoster without any complication with 15 days follow up.

Click here to view |

|

Table 2: Distribution of complications seen in herpes zooster patients

Click here to view |

Disccussion

Varicella Zoster is a ubiquitous DNA virus which belongs to sub family of human alpha herpes virus. Herpes zoster is an acute viral infection characterized by vesicular skin lesions which are usually distributed over several unilateral adjacentsensory dermatomes. It causes chicken pox and then remains latent for decades in cranial nerve, dorsal root and autonomic nervous system ganglia along the entire neuralax is.12 The classic presentation of HZ starts with aprodrome of mild- to-moderate burning or tingling (or in some cases numbness) in or under the skin of a given dermatome, often accompanied by fever, chills,headache, stomach upset, and general malaise. Within 48-72 hours from the prodrome, an erythematous, maculopapular rash forms unilaterally along the dermatome and rapidly develops into vesicular lesions reminiscent of the original chickenpox outbreak. The pain associated with shingles varies in intensity from mild to severe such that even the slightest touch or breeze can elicit excruciating spasms.13 The lesions usually begin to dry and scab 3-5 days after appearing. Total duration of the disease is generally between 7-10 days; however, it may take several weeks for the skin to return to normal. Involvement of the second and third branches of the trigeminal nerve results in vesicular lesions in oral cavity.

Complications associated with herpes zoster14 Cutaneous

Disseminated cutaneous zoster* Bacterial superinfection

Chronic atypical lesions with hyperkeratosis*

Recurrent zoster*

Neurological

Postherpetic neuralgia

Meningitis, myelitis, encephalitis*

Cranial nerve palsies including Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Granulomatous cerebral angiitis

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Ophthalmological

Keratitis

Chorioretinitis, progressive outer retinal necrosis*

Uveitis

Iridocyclitis

Secondary glaucoma

Cataract

Visceral

Gastrointestinal involvement (esophagitis, gastritis, colitis)*

Pneumonia*

Pericarditis

Cystitis

Hepatitis

*Most frequently seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly in those with marked reduction in CD4+ T cell counts

The most common complication associated with HZ is the development of post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), a condition where pain accompanying the rash persists long after the lesions have healed. This pain has been characterized as an unrelenting sharp, burning, stabbing pain, capable of making unbearable the most menial activities of everyday life, such as bathing or dressing. PHN is of particular concern with increasing age because it is estimated that half the individuals over age 50 who develop shingles also develop PHN. Other potential complications of HZ include encephalitis, myelitis, peripheral nerve palsies, and forms of contralateral hemiparesis.15 In the present study post-herpetic neuralgia was seen in 33.92 Majority of patients 41.07% were in the age group of 40-60 years. Male to female ratio of patients was 1.8:1 which is in accordance with study of Dubeyet al (2005) which showed 1.74 : 1.16 Latheefet al (2011) found a male: female ratio of 1.33: 1.17 Uddinet al (2010) found a male to female sex ratio was 1.4: 1.18 Kayasthaet al (2009) found among 174 cases 119 (68.39%) were males and 55 (31.61%) were females, the male: female ratio being 2.16: 1.19 Trauma and stress as a result of their occupation and out door activity may be the predisposing factor for the male preponderance in Indian rural setup. Paresthesia and burning sensation in the region of the affected nerve are also frequent consequences of the VZV infection. Paresthesia after resolution of zoster rash was seen in 30.35% of patients. Secondary infections were seen in 3.57% of patients. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (RHS), also called Herpes Zoster Oticus, is a rare, severe complication of Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) reactivation. The classic triad consists of otalgia, vesicles in the auditory canal and ipsilateral facial paralysis.20 Without treatment, full recovery of the facial paralysis occurs in as little at 20% of cases; this is much improved if treatment is started within 72 hours21. This rare complication was seen in 7.14% of patients.

Figure 3 and 4 showing a patient with vesicular eruptions on right half of face, intraoral on buccal mucosa, labial mucosa and tongue on right side, eruptions on external ear. The same patient latter on developed Ramsy hunt syndrome with inability to close right eye, absence of wrinkles on right side of forehead and inability to blow air inside cheeks. After treatment patient was able to close both eyes, blow air inside cheeks and reappearance of wrinkles on forehead meanwhile both inta and extra oral lesions also resolved.

|

Figure 3 : Patient with vesicular eruptions on right half of face

Click here to view |

|

Figure 4 : Patient with vesicular eruptions on buccal mucosa, labial mucosa and tongue on right side.

Click here to view |

8.92% of patients developed post herpetic itching and were very reluctant to treatment. A few experienced severe pain without any evidence of avesicular eruption (i.e., zoster sine herpete), and a small number of patients have a characteristic eruption but do not experience pain. Symptoms and lesions in the eruptive phase tend to resolve over 10-15 days. However, lesions may require up to a month to completely heal, and the associated pain may become chronic. Patients are infectious until the lesions have dried. Anyone who has not previously had Varicella is at risk of acquiring this readily transmitted virus. Pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients have the highest risk of serious sequelae. Therefore, early diagnosis and prompt treatment of the disease in the prodromal phase by the use of antiviral agents should probably be the mainstay of its management. Antiviral therapy has been shown to decrease the duration of HZ rash and the severity of pain associated with it.22 When HZ affects the first branch of the trigeminal nerve, serious damage of the eye might occur (zoster ophtalmicus).

Oral consequences of HZ might include heavy scarring, pulpal necrosis and internal root resorption. Also, cases of bone necrosis with teeth loss in immunocompromised patients with long term HZ have been described. Finally, patients suffering from recurrent HZ may have increased incidence of malignant diseases.23

Conclusion

Oral physicians should have a thorough knowledge about the presentation of this condition, its treatment and the possible complications.Differential diagnosis is very important to ensure that the correct treatment is performed. Because the manifestations of a trigeminal herpes zoster resemble to other oral entities the oral practitioners must beaware about the differential diagnosis and definitive treatment modalities before any dental therapy is applied and intraoral examination is necessary when skin facial lesions are observed by professionals. The disease preferentially involves older age group while being a rarity in children. Various precipitating factors and diseases may be associated with Herpes Zoster. Some forms of Herpes Zoster like Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus, Ramsay- Hunt Syndrome should be promptly diagnosed and treated because they always pose a risk for permanent damage of vital structures like the eye, ear or the facial nerve.

References

1. Wood MJ. History of Varicella Zoster virus. Herpes 2000; 7:60-65.

2. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, 2003.

3. Pavithran K. An clinical study of five hundred cases of herpes zoster. Antiseptic 1986; 83:682-5.

4. Peeneys N. Diseases caused by viruses. In: Elder D, editor. Lever’s Histopathology of the skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia:Lippincott - Raven; 1997. p. 569-89.

5. Whitley RJ. Varicella Zoster virus. In: Mandell GL, BennetJE,Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases.4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. p. 1345-51.

6. Schacker T, Corey L. Herpes virus infections in HIV infected person. In: Devita VT, Samuel Hailman, Lisenberg SA, editors.Textbook of AIDS. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven; 1997. p. 267-80.

7. Smith KJ, Skelton HG, Yeager J. Cutaneous findings in HIV 1 positive patients: A 42 - months’ prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 3:746-54.

8. Watson PN, Evens RJ. Post herpetic neuralgia: A review. Arch Neural 1986; 43:836-40.

9. Bernhard P, Obel N. Chronic ulcerating acyclovir resistant Varicella Zoster lesions in an AIDS patient. Scand J Infect Dis 1996; 27:623-5

10. Malathi N, Rajan ST, Thamizhchelvan, Sangeetha N. Herpes zoster: a clinicopathologic correlation with literature review. Oral Maxillofacial Path J 2014; 5(1):449-452

11. Bandral MR, Chidambar YS, Telkar S, Japatti S, Choudary L, Dodamani A. Oral complications of herpeszoster infection- report of 3 cases. Intl J Dental Clinics 2010; 2(4):70-75

12. Edgerton G. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus: areview of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol 1945; 34( 40 ):114-53.

13. Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, et al. Acute painin herpes zoster and its impact on health-relatedquality of life. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:342-8.

14. Boivin G, Jovey R, Elliott Ct, Patrick dM. Management andprevention of herpes zoster: a Canadian perspective. Can Jinfect dis Med Microbiol 2010; 21(1):45-52.

15. Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpeszoster. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:340-6.

16. Dubey AK, Jaisankar TJ, Thappa DM. Clinical and morphological characteristics of herpes zoster in South India. Indian J Dermatol 2005; 50:203-7.

17. Abdul Latheef EN, Pavithran K. Herpes Zoster. A clinical study in 205 patients. Indian J Dermatol 2011; 56:529-32

18. Uddin M R, Bhuyan MMH, Akhter F. Study on Morphological and Clinical Aspects of Herpes Zoster in a Tertiary Medical College Hospital. Medicine Today 2010; 22(2):80-2.

19. Chaudhary SD, Dashore A, Pahwa US. A clinico-epidemiologic profile of herpes zoster in North India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1987; 53:213-6.

20. Adour KK: Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol 1994; 35(Suppl 1):62-4.

21. Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, Honda N, Gyo K, Yanagihara N: Treatmentof Ramsay hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance ofearly diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol 1997; 41(3):353-7.

22. 22 Nurimiko, T, Bowsher, D. Somato sensory findings in post-herpetic neuralgia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 3:135-41.

23. Shaikh S, Ta CN. Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am Fam Physician 2002; 66(9):1723-30.