INTRODUCTION

Myxoma is defined as “a tumor composed of sometimes spindle-shaped cells set in a myxoid stroma containing mucopolysaccharide, through which course very delicate reticulin fibers in various directions and which is locally invasive.” Myxomas were first described by Virchow in 1871. Myxoma of the jaws was identified by Thoma in 1954, but epidemiologic data is scarce.1 Myxoma occurs both in bone and soft tissue. Although intraosseous myxoma has been reported in various anatomical sites the majority of these tumors occur in the mandible, followed by the maxilla. Hence the term “odontogenic myxoma” (OM) is often applied when the tumor occurs in the jaws to reflect its odontogenic origin.2

Odontogenic myxomas are rare slowly growing benign tumors derived from embryonic mesenchymal elements of dental anlage that represents about 3% of all odontogenic tumors with high recurrence rate.2,5

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), OM is classified as benign tumor of ectomesenchymal origin with or without odontogenic epithelium. OM appears to originate from dental papilla, follicle, or periodontal ligament. The evidence for its odontogenic origin arises from its almost exclusive location in the tooth bearing areas of the jaws, its occasional association with missing or unerupted teeth, and the presence of odontogenic epithelium.4,6

The odontogenic nature of the myxomas has been challenged by some authors because of the appearances, whilst consistent with odontogenic ectomesenchyme, could also represent a more primitive fibroblastic or undifferentiated tissue.7 Most of the OMs reported were young adults affected mostly in their second and third decade of life with marked female predilection.2, 4, 6, 7 Clinically, OMs are slow growing, painless, and locally aggressive tumors. Since pain and hypoesthesia are not common, the lesions may reach a considerable size before patient perceives its existence and seeks treatment. Larger lesions may cause tooth displacement and cortical bone expansion.7, 8

Radiologically, the appearance may vary from a unilocular radiolucency to a multicystic lesion with well-defined or diffuse margins with fine, bony trabeculae within its interior structure expressing a “honey combed,” “soap bubble,” or “tennis racket” appearance.4, 9 A unilocular appearance may be seen more commonly in children and in anterior parts of the jaws. Root resorption is rarely seen, and the tumor is often scalloped between the roots.8

OMs are not encapsulated, thus promoting significant infiltration into the adjacent medullar bone.7 It can be locally aggressive despite its slow growth, which is reflected in the fact that less than 1% of tumor cells are positive for the proliferation marker Ki-67.2 The OM exhibits abundant extracellular production of ground substance and thin fibrils by the delicate spindle-shaped cells.

These undifferentiated mesenchymal cells are capable of fibroblastic differentiation also. Depending upon the pattern of differentiation, the histological nature of the tumor varies. It may be completely myxomatous tissue or varying proportions of myxomatous and fibrous tissue.4, 7 Some studies show OM as a modified form of fibroma in which myxoid intracellular substance separates the connective tissue.4, 10

The treatment of choice for OM is surgical excision by enucleation, curettage, or block resection.7 Although small myxomas are generally treated by curettage, larger lesions require extensive resection. Since myxomas tend to recur, it is mandatory that the patients be carefully followed after the surgery. It is widely accepted that local infiltration accounts for its aggressive nature and high recurrence rate, resulting in sparsely scattered deposits of residual bone and dystrophic mineralization in the tumor stroma.2

Due to poor follow-up and lack of reports, a precise and accurate recurrence rate is still missing. The high recurrence rate of 25% is reported when more conservative treatments are used.7 The present case is discussed due to its rarity, large size, mandibular involvement, diagnostic and operative dilemmas encountered during its management.

CASE REPORT

A 22 year old female was admitted to department of Plastic surgery with complaints of swelling over the left lower jaw region for 1 year, showing facial deformity and slow progression in size. It was insidious in onset and associated with occasional pain over the swelling. On extraoral examination, a bony hard mass of size 7 x 5 cm was seen on the body of the left mandible, fixed to the mandible, non-tender with no local rise of temperature. Intraoral examination revealed a mass extending to the floor of mouth on left side, obstructing the left gingivo-labial sulcus and left 2nd molar tooth with caries noted. Radiological investigations-

OPG and X-Ray of left mandible showed tumor involving body of the mandible. It was multicystic, radiolucent tumor involving outer and inner table of body of the mandible.

|

Figure 1: Extraoral photograph, showing swelling in the Left-side Body of the mandible

Click here to view |

|

Figure 2: Panoramic radiograph showed a poorly defined, multilocular radiolucent lesion with “soap bubble” appearance on left side mandible

Click here to view |

|

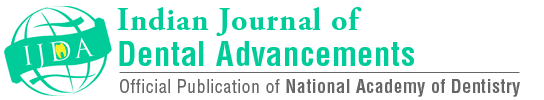

Figure 3: Postoperative picture showing reconstruction of the resected site with iliac bone grafting and fixation with titanium plate.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 4: Gross specimen of hemi-mandibulectomy with teeth attached measuring 6x6x4.5cm. Left 2nd molar tooth showing dental caries.

Click here to view |

|

Figure 5: Cut-surface showing grey white lesion with mucoid secretions

Click here to view |

|

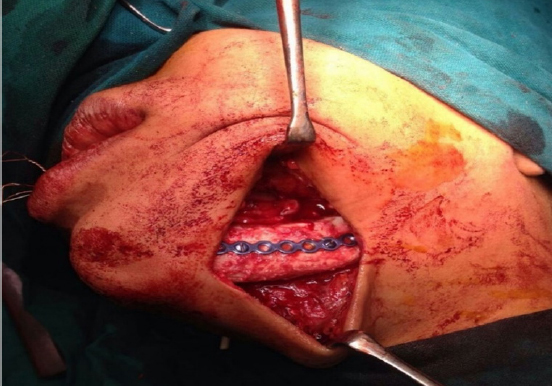

Figure 6: Microscopic examination showing stellate and spindle shaped cells having round to oval vesicular nuclei with eosinophilic cytoplasmic processes, embedded in myxoid stroma. (H&E, x40)

Click here to view |

A clinical diagnosis of Ameloblastoma was made and the patient was operated with Left side hemi-mandibulectomy with reconstruction of mandible with bone grafting from Iliac crest and the specimen was sent for histopathological examination. Post-operative recovery was excellent.

Grossly the hemi-mandibulectomy specimen with teeth attached was 6 x 6 x 4.5 cm and on cut-surface, was grey white, hard in consistency with mucoid secretions.

Microscopic examination showed stellate and spindle shaped cells having round to oval vesicular nuclei with eosinophilic cytoplasmic processes, embedded in myxoid stroma. Few thin walled vascular spaces were seen interspersed between the tumor cells.

Discussion

OM is a rare aggressive intraosseous lesion derived from embryonic mesenchymal tissue associated with odontogenesis and primarily consisting of a myxomatous ground substance with widely scattered undifferentiated spindled mesenchymal cells. Though it is a benign neoplasm, it may be infiltrative, aggressive and may recur.4

The prevalence of OM is principally quoted between 0.04% and 3.7%. In Asia, Europe, and America, relative frequencies between 0.5% and 17.7% have been reported.5, 7 There was lack of uniformity in the most common age group studies, but most of the studies showed an age range of 22.7 to 36.9 years, and it is rarely seen in patients younger than 10 years of age or older than 50.4, 7 In the present case age of the patient is 22 years, which is in conformity with the reported literature.

The mandible appears to be more frequently affected than the maxilla.2, 4, 8 The present case involves posterior mandible, which is almost in conformity with the reported literature. There are no clinical or radiological signs that would allow a physician to distinguish myxoma from odontogenic and non-odontogenic lesions; however, histological analysis shows several lesions that could be misinterpreted as myxoma.7

The majority of the myxomas are almost always asymptomatic, although some patients present with progressive pain in lesions invading into surrounding structures with eventual neurological disturbances. OM of the maxilla is less frequent but behaves more aggressively than that of the mandible.7 In the present case the patient complained of intermediate pain, and was more aggressive, in spite of its mandibular occurrence.

OMs radiographically appear as multilocular or unilocular radiolucencies. The present case showed multilocular radiolucency with “soap bubble” appearance. Differential diagnosis like ameloblastoma, ameloblastic fibroma, odontogenic fibroma, central hemangioma, or odontogenic keratocyst along with OM could be listed as initial diagnostic hypothesis based on the clinical and radiological findings.2, 4, 7

The aggressive nature of OM is well documented in the literature. The tumor is not radiosensitive, and surgery is the treatment of choice.2, 4, 6, 8

The lack of a capsule and infiltrative growth pattern is responsible for high rate of recurrence when conservative enucleation and curettage are performed. Recurrence is minimized with extensive partial or total resection procedures.2, 11 The conservative treatments have several advantages over more radical treatment, which would consist of mandibular reconstruction with fibular microsurgical flap. The treatment represents a less morbid intervention with the possibility of intraoral access, the absence of donor area, a shorter hospitalization time, not interfering with facial growth in children, and a low procedural cost. Radical treatment of block resection is advised by most authors over conservative treatment due to its invasive nature, large size, and recurrence history even though this intervention poses patients post treatment rehabilitation difficulties.4, 7, 9

The present case was treated with block resection as left side hemi-mandibulectomy with reconstruction of mandible with bone grafting from Iliac crest. A minimum of five years of surveillance is required to confirm that the lesion has healed, and periodical clinical and radiographic followup should be maintained indefinitely irrespective of treatment modality applied to treat OM.7

Conflict of Interest statement: Nil