|

|

| Line 32: |

Line 32: |

| | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> | | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | <h3 class="title">INTRODUCTION</h3> | | <h3 class="title">INTRODUCTION</h3> |

| − | | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">The innate immune system is critical for the defense against pathogenic microorganisms. The host faces major challenges from microbial pathogens escaped from the host immune system. The innate immune system which act as first line of defense, relies on the presence of pattern recognition receptors, including membrane-bound Toll-like receptors, retinoid- inducible gene 1-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors and nucleotide-binding- domain-like receptors, to recognize various pathogens and their components.<a href="#ref1"><font face="Arial" size=".8">1</font></a>, <a href="#ref2"><font face="Arial" size=".8">2</font></a> These special receptors are expressed by macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes and epithelial cells. They respond to ’pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP)’ and ’danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMP). DAMPs are of host derived (ATP, DNA or cholesterol crystals) or environmentally (asbestos, silica) derived.<a href="#ref3"><font face="Arial" size=".8">3</font></a> The activation of pattern recognition receptors by PAMPs and DAMPs leads to activation of specific inflammatory response by ’inflammasome’ complex.</p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;"><span><b>Inflammasome:</b></span> The term ’inflammasome’ was coined by Jurg Tschopp and his research team in 2002. Inflammasome complex is nucleotide-binding- domain-like receptors containing multi protein complexes. They are activated by exposure to cellular danger or stress signals, which trigger release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1ß (IL-1) and interleukin-18(IL-18).<a href="#ref4"><font face="Arial" size=".8">4</font></a> Nucleotide-binding-domain-like receptors (NLRs) are a family of intracellular immune receptors which consists of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) near the C terminus and a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD). The LRR domain plays role in auto regulation, the recognition of PAMPs and protein-protein interactions. The NBDs regulates self- oligomerization.<a href="#ref5"><font face="Arial" size=".8">5</font></a>, <a href="#ref6"><font face="Arial" size=".8">6</font></a></p> |

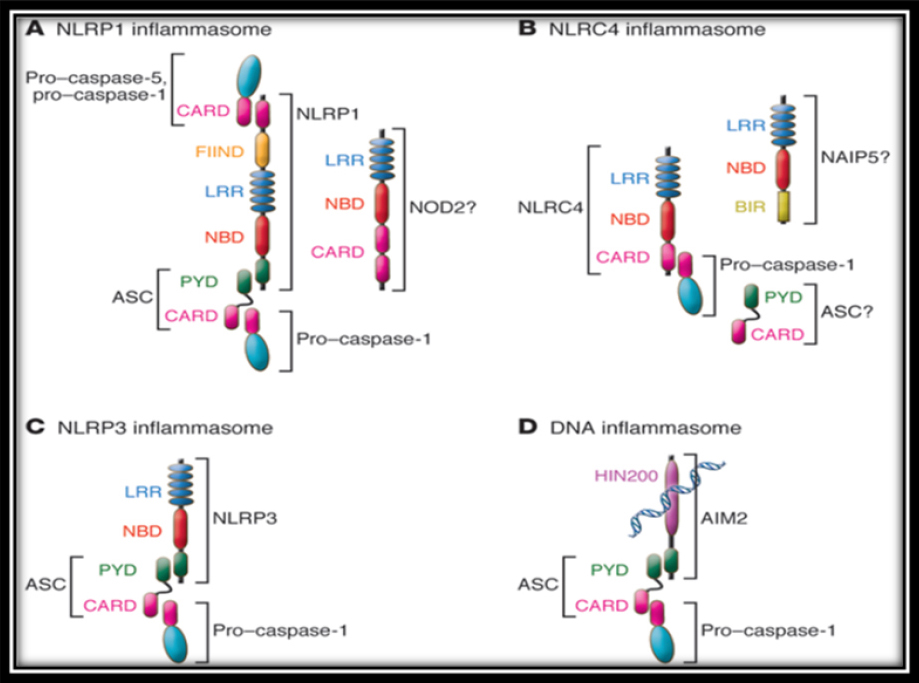

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">NLRs differ in their N-terminal domains.<a href="#ref7"><font face="Arial" size=".8">7</font></a> The largest group contains 14 members which have N- terminal pyrin domain (PYD). Another group contains an N-terminal caspase recruitment domain (CARD), and other group contains nucleotide- binding oligomerization domains (NOD) Other NLR family members contains an acidic transactivation domains. Several members of the NLR family assemble as multi molecular complexes in response to various activators, leading to the activation of inflammatory caspases. Activated caspase-1 controls the maturation of the cytokines of the IL-1 family. These NLRs complexes are called inflammasome. The inflammasome are NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4 and AIM2 (<a class="ref" href="http://rep.nacd.in/ijda/08/02/images/IJDA-8-94-g001.jpg" target="_blank">Figure 1</a>) which belongs to a different protein family (PYHIN).<a href="#ref8"><font face="Arial" size=".8">8</font></a>-<a href="#ref11"><font face="Arial" size=".8">11</font></a></p> |

| | + | <table width="100%" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1"> |

| | + | <tr> |

| | + | <td align='center' bgcolor="f3f3f3" width='200px'><img src='http://rep.nacd.in/ijda/08/02/images/IJDA-8-94-g001.jpg' height="95" alt='' style="padding:3px;"/> |

| | + | <td bgcolor="eaeaea" style="padding:5px;"> |

| | + | <font class='ref'>Figure 1: Nucleotide-binding-domain-like receptors (NLRs)</font> |

| | + | <br/> |

| | + | <br/> |

| | + | <a class="ref" href="http://rep.nacd.in/ijda/08/02/images/IJDA-8-94-g001.jpg" target="_blank"> |

| | + | <b>Click here to view</b> |

| | + | </a> |

| | + | </td> |

| | + | </tr> |

| | + | </table> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Inflammasome can control the mediation of proinflammatory responses in a group of chronic diseases, such as gout, cancer and bacterial and viral infections.<a href="#ref2"><font face="Arial" size=".8">2</font></a>, <a href="#ref12"><font face="Arial" size=".8">12</font></a> The dysregulation of inflammasome components are associated with various inherited chronic inflammatory and immune disorders.<a href="#ref3"><font face="Arial" size=".8">3</font></a> In particular, the imbalance of interleukin-1ß activity is among the focal points of both microbial- associated and non microbial inflammatory diseases. The progression of periodontitis is inflammatory in nature, with the main triggers of oral inflammation usually residing in the oral micro biome and the balance of its components.<a href="#ref13"><font face="Arial" size=".8">13</font></a></p> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome</h3> |

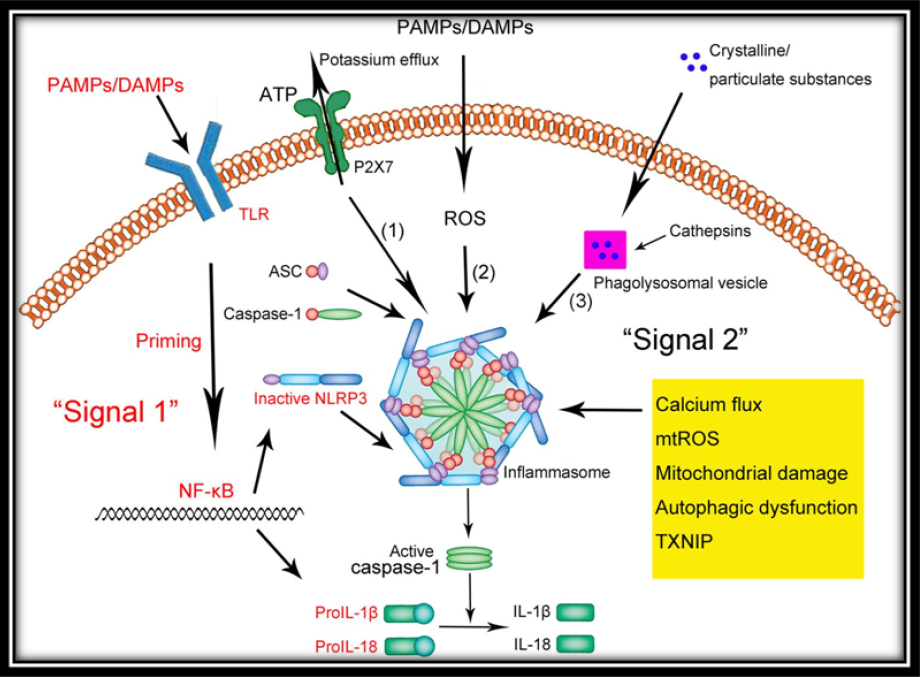

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">NLRP3 is one of the best characterized nucleotide- binding-domain-like receptor family which plays a key role in the induction of pro-inflammatory host responses.<a href="#ref14"><font face="Arial" size=".8">14</font></a> Microbial infection individual microbial components and host-derived small danger molecules, such as extracellular ATP activates NLRP3. <a href="#ref15"><font face="Arial" size=".8">15</font></a>-<a href="#ref17"><font face="Arial" size=".8">17</font></a> The stimulated NLRP3 binds to caspase-1, leads to the activation of caspase-1, which ultimately cleaves pro- interleukin-1ß and pro-interleukin-18 into their biologically active mature forms.<a href="#ref4"><font face="Arial" size=".8">4</font></a></p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">NLRP3 inflammasome activation generally requires two signals (<a class="ref" href="http://rep.nacd.in/ijda/08/02/images/IJDA-8-94-g002.jpg" target="_blank">Figure 2</a>):</p> |

| | + | <table width="100%" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1"> |

| | + | <tr> |

| | + | <td align='center' bgcolor="f3f3f3" width='200px'><img src='http://rep.nacd.in/ijda/08/02/images/IJDA-8-94-g002.jpg' height="95" alt='' style="padding:3px;"/> |

| | + | <td bgcolor="eaeaea" style="padding:5px;"> |

| | + | <font class='ref'>Figure 2: Inflammasome Signaling Pathway</font> |

| | + | <br/> |

| | + | <br/> |

| | + | <a class="ref" href="http://rep.nacd.in/ijda/08/02/images/IJDA-8-94-g002.jpg" target="_blank"> |

| | + | <b>Click here to view</b> |

| | + | </a> |

| | + | </td> |

| | + | </tr> |

| | + | </table> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">I. The first signal is induced when PAMPs stimulate a pattern- recognition receptor and leads to production of the interleukin-1 precursor.<a href="#ref18"><font face="Arial" size=".8">18</font></a></p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">II. The second signal is induced by DAMPs</p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">A growing number of research findings are highlighting the crucial role of extracellular ATP in the regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through purinergic receptors (P2X).<a href="#ref19"><font face="Arial" size=".8">19</font></a> The significance of the P2X7 receptor is widely studied in myeloid cells, such as monocytes, macrophages and dentritic cells. The role of P2X7 in epithelial cells is recently explored. Gingival epithelial cells which are first line of innate immunity, express functional P2X7 receptors.<a href="#ref20"><font face="Arial" size=".8">20</font></a>, <a href="#ref21"><font face="Arial" size=".8">21</font></a> Recent studies have shown the role of P2X7 in the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn leads to the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.<a href="#ref22"><font face="Arial" size=".8">22</font></a>, <a href="#ref23"><font face="Arial" size=".8">23</font></a></p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Potential mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation</h3> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Currently, there are three models for activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome:</p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:0pt; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;"> |

| | + | <div class="list"> |

| | + | <ul style="list-style-type: none"> |

| | + | <li><p>1) The reactive oxygen species (ROS) model</p></li> |

| | + | <li><p>2) The lysosomal burst model</p></li> |

| | + | <li><p>3) The ATP-triggered K+-efflux model</p></li> |

| | + | </ul> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | </p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Inflammasome signaling and periodontal disease</h3> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Inflammasome complexes play a pivotal role in periodontal disease and the inflammasome- associated inflammatory mediators involved in the progression of the disease have been highlighted through several clinical studies. <a href="#ref24"><font face="Arial" size=".8">24</font></a>-<a href="#ref26"><font face="Arial" size=".8">26</font></a> The relationship between the IL-1 cytokine family and the NLRP3 inflammasome complex has been studied recently.<a href="#ref24"><font face="Arial" size=".8">24</font></a> The findings of this study showed higher levels of NLRP3, NLRP2, IL-1 β and IL-18 mRNA in gingival tissue samples from patients with periodontal disease and also showed a positive correlation between NLRP3 and expression of IL-1 β and IL-18 in periodontal disease.<a href="#ref24"><font face="Arial" size=".8">24</font></a> Certain species of periodontal bacteria, such as P. gingivalis(pg), Treponema denticola(td), Tannerella forsythia (tf) and Eubacterium nodatum, were showed correlation with IL-1 β and IL-18 in GCF who suffered with chronic periodontitis.<a href="#ref26"><font face="Arial" size=".8">26</font></a></p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Key players in periodontal disease and inflammasome signaling</h3> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. g)</h3> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Porphyromonas gingivalis is a gram-negative host-adapted anaerobe and a prominent bacterium present in the tissues of patients with chronic severe periodontitis.<a href="#ref21"><font face="Arial" size=".8">21</font></a>, <a href="#ref27"><font face="Arial" size=".8">27</font></a>, <a href="#ref28"><font face="Arial" size=".8">28</font></a> Pg plays a key role in both oral and systemic diseases.<a href="#ref13"><font face="Arial" size=".8">13</font></a>, <a href="#ref29"><font face="Arial" size=".8">29</font></a> It showed distinct mechanisms for manipulating host inflammatory responses, such as reducing the innate immune response for its own benefit and, simultaneously, providing a favorable environment for co-habitants, such as F. nucleatum and T. denticola.<a href="#ref30"><font face="Arial" size=".8">30</font></a> It showed significant down-regulation of the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1ß was seen in periodontal tissues when P. gingivalis was introduced in a subgingival biofilm.<a href="#ref31"><font face="Arial" size=".8">31</font></a> But in macrophages, NLRP3 inflammasome was up regulated in the presence of P. gingivalis and leads to increased levels of IL-1 β which results highly inflammatory cell death known as ’pyroptosis’. P. gingivalis can inhibit the extracellular ATP- P2X7 pathway by directly preventing inflammasome activation through secreting an effector called ’nucleoside diphosphate kinase’.<a href="#ref20"><font face="Arial" size=".8">20</font></a> Silencing of pannexin-1 expression in gingival epithelial cells resulted in the inhibition of extracellular ATP release during P. gingivalis infection, highlighting the importance of pannexin-1 in activation of the inflammasome and secretion of interleukin-1 β.<a href="#ref20"><font face="Arial" size=".8">20</font></a></p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa)</h3> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans has been closely associated with the loss of periodontal tissue attachment in affected sites of both adults and juveniles. The presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans is a well-identified indicator of the initiation of localized aggressive periodontitis.<a href="#ref32"><font face="Arial" size=".8">32</font></a> The pathogenicity of the microorganism is also underlined by its well- characterized virulence factors, such as leukotoxin and cytolethal distending toxin, which are suggested to play important roles in altering host inflammatory responses as well as in contributing to periodontal disease progression.<a href="#ref33"><font face="Arial" size=".8">33</font></a></p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">A. actinomycetemcomitans up regulates NLRP3, IL 1β and down regulates NLRP6 in peripheral mononuclear leukocytes. The bacterial leukotoxin induced an excessive proinflammatory response in macrophages, through the secretion of IL-1 β and IL-18 and the involvement of purinergic receptor P2X7 in the process.<a href="#ref34"><font face="Arial" size=".8">34</font></a> In contrast, in another in vitro study leukotoxin and cytolethal distending toxin gene knockout mutant strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans were used to infect human mononuclear leukocytes, only up-regulation of NLRP3, interleukin- 1β, interleukin-18 and reduction of NLRP6 were observed.<a href="#ref31"><font face="Arial" size=".8">31</font></a> Based on the results of this study, there was possible regulation of inflammasome complexes by additional molecules other than the two best-studied virulence factors of the microorganism. A potential candidate may be ’bacterial IL-1 β receptor I’, a putative membrane protein of A. actinomycetemcomitans, which was found to bind IL-1 β.<a href="#ref35"><font face="Arial" size=".8">35</font></a></p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Although ’bacterial IL-1 β receptor I’ role is not identified clearly. There is a need for future studies addressing the role of host immune signaling cascades which are involved in the virulence of this pathogen.</p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title1">Candida albicans</h3> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Candida albicans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that commonly resides on human mucosal surfaces and, when overgrown under immuno compromised conditions, causes inflammation and other systemic infections.<a href="#ref36"><font face="Arial" size=".8">36</font></a> One of the most characterized virulence-associated factors belongs to the family of the ’secretion of aspartic proteases’, which has been shown to induce secretion of pro- inflammatory cytokines in human monocytes.<a href="#ref37"><font face="Arial" size=".8">37</font></a></p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">A recent in vitro discovery demonstrated that secretion of asparticproteases-2 and -6 specifically were responsible for inducing interleukin-1beta and interleukin-18 production in human monocytes as a result of activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1.</p> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Another study showed that both NLRC4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes were important in the induction of secretion IL-1 β. These studies demonstrate the ability of C. albicans to induce excessive inflammatory responses.<a href="#ref38"><font face="Arial" size=".8">38</font></a></p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title">CONCLUSION</h3> |

| | + | <p style="text-indent:1.5em; text-align:justify; margin-top:0.5em; margin-bottom:0.5em;">Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease. Innate immune system in periodontal disease plays a vital role in arresting of the disease. Besides other components of innate immune system, the inflammasome play a key role in the arrest of periodontal disease by activation of pro inflammatory cytokines and regulation of immune system.</p> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div class="back" id="article-back"> |

| | + | <div class="back-section"> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <font face="Arial" color="black" size="2"> |

| | + | <h3 class="title">REFERENCES</h3> |

| | + | <div> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref1">1.</a> Abdul-Sater AA, Said-Sadier N, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz O, Kelly KA. Inflammasomes bridge signaling between pathogen identification and the immune response. Drugs Today 2009; <span><b>45</b></span>: 105-112.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref2">2.</a> Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; <span><b>27</b></span>: 229-265.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref3">3.</a> Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell 2010; <span><b>140</b></span>: 821-832.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref4">4.</a> Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of pro IL-1 beta. Mol Cell 2002; <span><b>10</b></span>: 417-426.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref5">5.</a> Duncan, Bergtralh, Wang, Willingham. Cryopyrin/NALP3 binds ATP/dATP, is an ATPase, and requires ATP binding to mediate inflammatory signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007; <span><b>104</b></span>: 8041-8046.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref6">6.</a> Ye Z, Lich JD, Moore CB, Duncan JA. ATP binding by monarch-1/ NLRP12 is critical for its inhibitory function. Mol. Cell. Biol.2008; <span><b>28</b></span>: 1841-1850.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref7">7.</a> Ting, Jerry P, Lineberger. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity 2008; <span><b>28</b></span>: 285-287.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref8">8.</a> Buerckstuemmer T, Baumann, Dixit, Jahn. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol 2009; <span><b>10</b></span>: 266-2672.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref9">9.</a> Fernandes-Alnemri, Yu, Datta and Alnemri. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature 2009; <span><b>458</b></span>: 509-513.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref10">10.</a> Hornung, Ablasser, Charrel, Bauernfeind. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature 2009; <span><b>458</b></span>: 514-518.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref11">11.</a> Roberts, Idris A, Dunn JA, Kelly GM. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science 2009; <span><b>323</b></span>: 1057-1060.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref12">12.</a> Drexler SK, Yazdi AS. Complex roles of inflammasomes in carcinogenesis. Cancer J 2013; <span><b>19</b></span>: 468-472.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref13">13.</a> Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Breaking bad: manipulation of the host response by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Eur J Immunol 2014; <span><b>2</b></span>: 328-338.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref14">14.</a> Latz E. The inflammasomes: mechanisms of activation and function. Curr Opin Immunol 2010; <span><b>22</b></span>: 28-33.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref15">15.</a> Jin C, Flavell RA. Molecular mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Clin Immunol 2010; <span><b>30</b></span>: 628-631.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref16">16.</a> Kim JJ, Jo EK. NLRP3 inflammasome and host protection against bacterial infection. J Korean Med Sci 2013; <span><b>28</b></span>: 1415-1423.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref17">17.</a> Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Modulation of inflammasome pathways by bacterial and viral pathogens. J Immunol 2011; <span><b>187</b></span>: 597-602.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref18">18.</a> Janeway CA Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 2002; <span><b>20</b></span>: 197-216.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref19">19.</a> Gombault A, Baron L, Couillin I. ATP release and purinergic signaling in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front Immunol 2012; <span><b>3</b></span>: 414.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref20">20.</a> Choi CH, Spooner R, DeGuzman J, Koutouzis T, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz O. Porphyromonas gingivalis-nucleoside- diphosphate- kinase inhibits ATP-induced reactive-oxygen- species via P2X7 receptor/NADPH-oxidase signalling and contributes to persistence. Cell Microbiol 2013; <span><b>15</b></span>: 961-976.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref21">21.</a> Yilmaz O, Yao L, Maeda K, Rose TM, Lewis EL, Duman M, Lamont RJ, Ojcius DM. ATP scavenging by the intracellular pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis inhibits P2X7- mediated host-cell apoptosis. Cell Microbiol 2008; <span><b>10</b></span>: 863-875.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref22">22.</a> Di Virgilio F. Liaisons dangereuses: P2X(7) and the inflammasome. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2007; <span><b>28</b></span>: 465-472.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref23">23.</a> Hung SC, Choi CH, Said-Sadier N, Johnson L, Atanasova KR, Sellami H, Yilmaz O, Ojcius DM. P2X4 assembles with P2X7 and pannexin-1 in gingival epithelial cells and modulates ATP-induced reactive oxygen species production and inflammasome activation. PLoS ONE 2013; <span><b>8:</b></span> e70210.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref24">24.</a> Bostanci N, Emingil G, Saygan B, Turkoglu O, Atilla G, Curtis MA, Belibasakis GN. Expression and regulation of the NALP3 inflammasome complex in periodontal diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 2009; <span><b>157</b></span>: 415-422.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref25">25.</a> Orozco A, Gemmell E, Bickel M, Seymour GJ. Interleukin- 1beta, interleukin-12 and interleukin-18 levels in gingival fluid and serum of patients with gingivitis and periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2006; <span><b>21</b></span>: 256-260.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref26">26.</a> Teles R, Sakellari D, Teles F, Konstantinidis A, Kent R, Socransky S, Haffajee A. Relationships among gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers, clinical parameters of periodontal disease, and the subgingival microbiota. J Periodontol 2010; <span><b>81</b></span>: 89-98.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref27">27.</a> Avila M, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz O. The oral microbiota: living with a permanent guest. DNA Cell Biol 2009; <span><b>28</b></span>: 405-411.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref28">28.</a> Sheets SM, Potempa J, Travis J, Casiano CA, Fletcher HM. Gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 induce cell adhesion molecule cleavage and apoptosis in endothelial cells. Infect Immun 2005; <span><b>73</b></span>: 1543-1552.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref29">29.</a> Atanasova KR, Yilmaz O. Looking into the Porphyromonas gingivalis’ cabinet of curiosities: the microbium, the host and cancer association. Mol Oral Microbiol 2014; <span><b>29</b></span>: 55-66.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref30">30.</a> Jenkinson HF, Lamont RJ. Oral microbial communities in sickness and in health. Trends Microbiol 2005; <span><b>13</b></span>: 589-595.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref31">31.</a> Belibasakis GN, Guggenheim B, Bostanci N. Down- regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome in gingival fibroblasts by subgingival biofilms: involvement of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Innate Immun 2013; <span><b>19</b></span>: 3-9.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref32">32.</a> Fine DH, Markowitz K, Furgang D, Fairlie K, Ferrandiz J, Nasri C, McKiernan M, Gunsolley J. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and its relationship to initiation of localized aggressive periodontitis: longitudinal cohort study of initially healthy adolescents. J Clin Microbiol 2007; <span><b>45</b></span>: 3859-3869.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref33">33.</a> Feng ZM, Weinberg A. Role of bacteria in health and disease of periodontal tissues. Periodontol 2000 2006; <span><b>40</b></span>: 50-76.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref34">34.</a> Kelk P, Abd H, Claesson R, Sandstrom G, Sjostedt A, Johansson A. Cellular and molecular response of human macrophages exposed to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Cell Death Dis 2011; <span><b>2</b></span>: 126.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref35">35.</a> Paino A, Ahlstrand T, Nuutila J, Navickaite I, Lahti M, Tuominen H, Valimaa H, Lamminmaki U, Pollanen MT, Ihalin R. Identification of a novel bacterial outer membrane interleukin- 1beta-binding protein from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. PLoS ONE 2013; <span><b>8:</b></span> e70509.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref36">36.</a> Tomalka J, Ganesan S, Azodi E, Patel K, Majmudar P, Hall BA, Fitzgerald KA, Hise AG. A novel role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in mucosal defenses against the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 2011; <span><b>7</b></span> : e1002379.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref37">37.</a> Naglik J, Albrecht A, Bader O, Hube B. Candida albicans proteinases and host/pathogen interactions. Cell Microbiol 2004; <span><b>6</b></span>: 915-926.</font></p> |

| | + | <p class="ref-label"><font face="Arial" color="black" size="1"><a name="ref38">38.</a> Pietrella D, Pandey N, Gabrielli E, Pericolini E, Perito S, Kasper L, Bistoni F, Cassone A, Hube B, Vecchiarelli A. Secreted aspartic proteases of Candida albicans activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol 2013; <span><b>43</b></span>: 679-692.</font></p> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | </font> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | </div> |

| | </body> | | </body> |

| | </html> | | </html> |

| | + | |