INTRODUCTION

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), the most common oral mucosal malignant tumor, diagnosis of which is seldom difficult. Use of radiation therapy to treat cancer which is routinely in practice inevitably involves exposure of normal tissues along with affected tissues. As a result, patients may experience symptoms associated with damage to normal tissue.1 Based on this strong evidence, it would be useful to know if and to what extent radiotherapy causes genotoxic and cytotoxic effects resulting in DNA damage on oral mucosa. In the present study, we investigated the effects of radiation therapy on the affected tissues along with unaffected tissues of patients diagnosed with SCC of oral cavity to evaluate cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of exfoliated oral mucosal cells.

AIMS & OBJECTIVES

To evaluate DNA damage (Micronucleus) and cellular death (Pyknosis, karyolysis and karyorhexis) of oral exfoliated cells from both exposed side & unexposed side in Individuals before & after radiotherapy. To compare cytotoxicity in patients before and during radiation therapy between different weeks. To compare cytotoxicity and genotoxic effects in different layers of oral mucosa of patients undergoing radiotherapy.

MATERIAL & METHODS

The study was designed to evaluate and to compare the cytotoxic and genotoxic changes of exfoliated oral mucosal cells of affected tissues along with unaffected tissues of patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity undergoing radiation therapy for a time period of six weeks. The present study was conducted in the MNJ cancer hospital, lakdikapul, Hyderabad. Materials used for the study were wooden spatulas, microscopic slides along with papanicolaou stain. The sampling technique was that smears were collected before radiation and during the radiation therapy from first week to sixth week. With a sterilized, moistened wooden spatula the buccal mucosa was gently scraped (Figure 1). The cells were immediately smeared on pre-cleaned microscopic slides and fixed immediately by suspension in absolute alcohol. The smears which were fixed with absolute alcohol are subjected to PAP staining procedure.

|

Figure 1: Buccal scrapings of affected area collected with wooden spatula.

Click here to view |

RESULTS

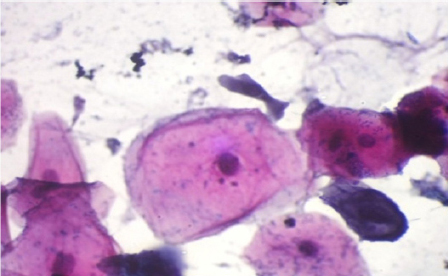

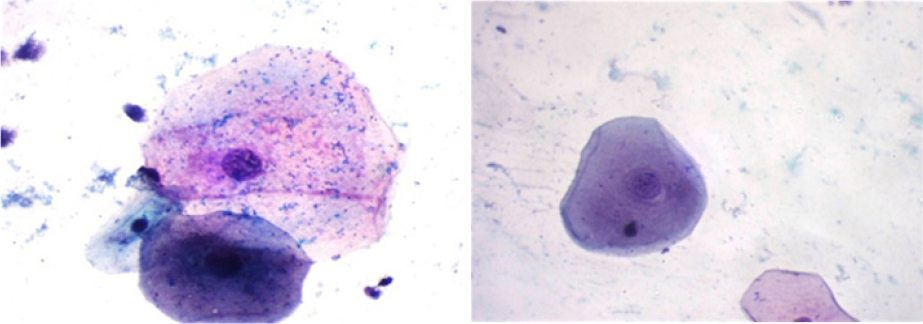

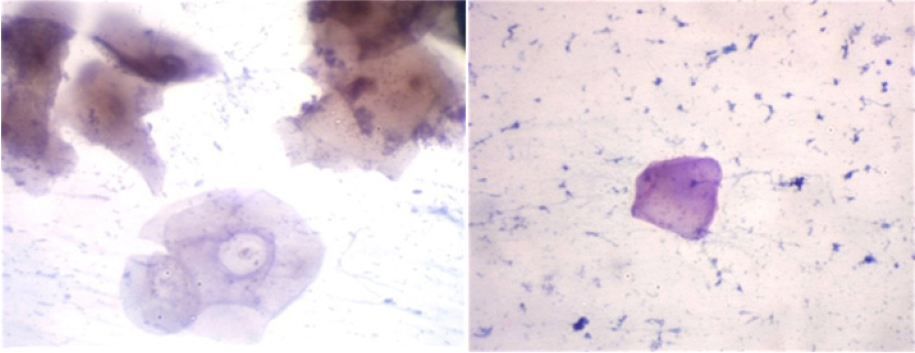

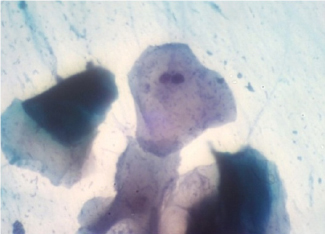

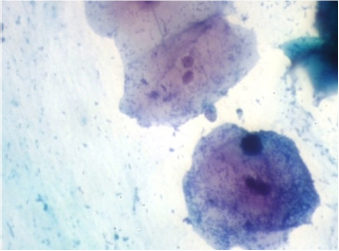

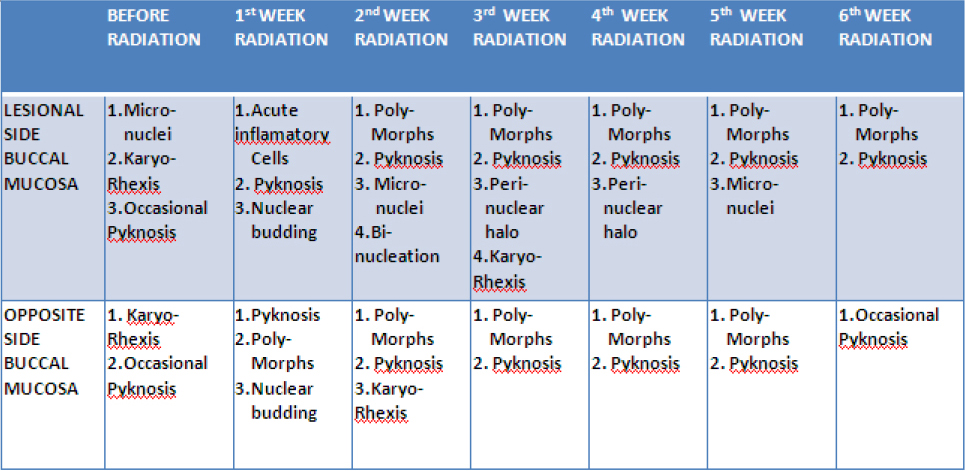

The results showed micronuclei on lesional side of buccal mucosa with karyorhexis and occasional pyknosis on both lesional and opposite side before radiation (Figure 2, 3 and 4). First week after radiation revealed acute inflammatory cells, pyknosis and nuclear budding on both affected and unaffected side (Figure 5). Polymorphs and pyknosis were seen on both the sides of buccal mucosa whereas micronuclei and binucleation (Figure 6) were seen only in affected side after second week. After third week perinuclear halo along with karyorhexis was seen on the lesional side. The same results were noticed even after fourth week. Micronuclei were seen on the lesional side along with polymorphs and pyknosis on both lesional side and opposite side after fifth week of radiation.Finally after sixth week of radiation only polymorphs with pyknosis were seen on lesional side and occasional pyknosis on the unaffected side of the buccal mucosa. The results were tabulated and shown in table 1.

|

Figure 2: Cells showing Micronuclei

Click here to view |

|

Figure 3: Cells showing Karyolysis and Karyorhexis

Click here to view |

|

Figure 4: Cells showing Pyknosis

Click here to view |

|

Figure 5: Cells showing Nuclear Budding

Click here to view |

|

Figure 6: Cells showing Binucleation.

Click here to view |

|

Table 1: Showing the results:

Click here to view |

DISCUSSION

SCC the most common oral mucosal malignant tumor, diagnosis of which is seldom difficult. It is the cancer staging and histopathological grading that are more important and micronuclei are good prognostic indicators. Different diagnostic methods such as routine histopathology (H and E-stained sections), exfoliative cytology, and immunohistochemistry are available today. Damage to oral mucosa in SCC is strongly related to radiation dose, fraction size, volume of irradiated tissue, fractionation scheme, and type of ionizing irradiation.1

Mucositis induced by radiotherapy is defined as the reactive inflammation of the oral and oropharyngeal mucous membrane during radiotherapy in the head and neck region. It is characterized by atrophy of squamous epithelial tissue, absence of vascular damage, and an inflammatory infiltrate concentrated at the basement region.2

The first clinical signs of mucositis occur at the end of the first week of a conventional seven-week radiation protocol (daily dose of 2 Gy, five times a week). Others consider erythema to be the first reaction.3 The lack of formation of new basal cells caused by radiotherapy leads to a gradual, linear decrease in cell numbers. As radio- therapy continues, a steady state between mucosal cell killing and mucosal cell regeneration may occur and favor an acute reaction in the form of a prominent erythema. Around the third week of radiotherapy, more severe symptoms of mucositis, such as the formation of pseudomembranes and ulceration, may appear.4 When radiotherapy commences, as a cell regeneration process that cannot keep up with cell killing. As a result, partial or complete epithelial denudation develops, which presents as spotted or confluent pseudomembranous mucositis. Healing eventually occurs from the surviving mucosal stem cells. The severity of mucositis varies considerably between patients (Denham et al., 1999) and may relate to the fractionation schedule applied. Mucositis is basically a tissue reaction to the trauma of radiation or chemotherapy.1, 5 In summary, although the etiopathogenesis of radiation mucositis still is not fully clear, it most likely can be considered as a four-step inflammation consisting of an inflammatory/vascular phase, an epithelial phase, a bacterial phase, and a healing phase. This sequence of phases has been pro- posed by Sonis (1998) for chemotherapy-induced stomato-tox- icity, but probably also holds true for radiation mucositis.6

Radiation injury is classified as

-

Acute (early) effects -observed during the course of treatment or within a few weeks after treatment.

-

Consequential effects -caused by persistent acute damage.

-

Late effects - emerge months to years after radiation exposure.

Treatment-related factors include the total dose, the dose per fraction, and schedule of treatment.

Cytogenetic analyses for chromosomal alterations in human are the most sensitive techniques for biomonitoring human radiation exposure. The results display an encouraging success rate for identifying premalignant and malignant lesions. ’Intrapatient’ normal smears provide a satisfactory control for comparison with pathological smears. Early results indicate that quantitative cytology could be of great value for monitoring and follow-up of suspicious lesions and provide an excellent additional diagnostic test for detecting early oral malignancy. This is in correlation with same findings as done by Cowpeetal.7, 8

The results of the present study were correlating with that of results obtained by Ogden etal,9,10 i.e the effect of radiotherapy on normal buccal mucosa was investigated using the quantitative techniques of cytomorphology (measurement of nuclear and cytoplasmic area) and DNA cytophotometry. These techniques were applied to smears obtained before, during, and after irradiation. Nuclear area and cytoplasmic area increased and DNA values were abnormal in most cases as a result of radiotherapy, returning to within normal limits one month after treatment.

Progress in cancer research is being made in many biologicaland technological areas. As cancer therapy improves and more patients survive longer, efforts are needed to direct research towards elucidating the processes that lead to complications of therapy. One must learn more about the similarities and differences between injury caused by radiation and that produced by other cytotoxic agents,surgery, and trauma. Furthermore, one must also find out more about the process of wound healing if we are to prevent or repair damage from ionising radiation and other anticancer therapies. Information from the study of damage to normal tissues caused by radiation are likely to be applicable to other cancer therapies and also to accidental or intentional radiation exposure.

OBSERVATIONS

Late effects were less severe and better local tumor control rates achieved with multiple, small radiation fractions than with a few large fractions.

CONCLUSION

Frequency of buccal mucosal cell micronuclei was not found to be increased following radiation compared with frequency prior to radiation exposure. Increased cytotoxic & genotoxic effects in oral mucosal cells seen in patients exposed before & after 1st two weeks of radiotherapy. The effects gradually decreased after 4th week radiotherapy, suggesting POSITIVE RESPONSE to radiotherapy. Changes were seen Predominately in Superficial Squamous Epithelial cells.